While recently searching for Tom Koehler’s obituary, I was delighted to find Johnson and Crawford’s (2022) excellent “A Brief History of Archaeology at Ole Miss.” After reading it, I felt that fans of Ole Miss archaeology may also find it interesting to read about the department as it appeared to one of its undergraduates nearly 60 years ago.

Like many freshmen, I arrived on campus in 1965 without having given serious thought to a prospective major, or frankly, what I was going to do with a university degree. My new roommate was passionately interested in archaeology and argued that I should consider taking an introductory Anthro class. Back then, long before the advent of personal computers, the course registration process required students to crowd into a campus gym at their assigned times and go from table to table signing up for the classes offered that semester. Grouped by department, all but one of the registration tables in the gym looked pretty much the same. The exception was the Soc/Anth table, behind which sat Tom Koehler. With his beard, very un-Mississippi suit, gregarious personality, and, later, his black eye patch, Tom stood out like a dumpster fire in a vacant lot. He was a good ad for the Soc/Anth department and I joined others to sign up for Soc/Anth classes.

Bob Thorne was my first anthropology instructor. A young man with a personality just as strong and engaging as Tom’s, Bob joined the Ole Miss faculty after he finished his MA in Anthropology as one of Tom’s advisees. Even as a new instructor, he had an easy-going manner in the classroom, one that effectively communicated the course material while at the same time making each class meeting seem more like a casual conversation. He was also the first college professor I met who wore cowboy boots with a suit. Having grown up down on the coast, where it was not unknown for a yacht club commodore to show up for events wearing shorts, flip-flops, and a navy blazer, cowboy boots were new for me. I bummed a ride to the boot store in Pontotoc and bought myself a pair.

By the beginning of my sophomore year, I was hooked. I declared an Anthropology major and a German minor and asked Bob and Tom about volunteering opportunities that would get me some field and lab experience. This led to the archaeology museum, which was tucked away in the corner of a building beyond the Grove on the east side of campus and to the lab in its basement, where I was put to work with other students labeling sherds, washing rocks, and doing all the other typical grunt work that falls to the lot of undergrad archaeology lab volunteers. Later that semester, I got my first archaeological excavation experience on a small field project run by John Connaway on the edge of Sardis Lake.

Many of our undergrad majors spent a lot of time in the archaeology lab, sometimes doing useful work, but often just studying or sitting around talking. One task that Shelia Landreth and I were given was to go through Bill Sanders’ boxes of Veracruz ceramics, which took up a lot of space in the collections storage room, separate out the rims and decorated sherds, and dispose of the rest. Given that Johnson and Crawford mention in their write-up that boxes of plain sherds from this project were still hanging around the lab more than 50 years later, we clearly did not do a very thorough job.

We did, however, end up with hundreds of pounds of plain body sherds and no obvious way to dispose of them. It was finally suggested that we should dump them in a river. To the best of my memory, Shelia borrowed a truck and we loaded up the sherds and hauled them to a bridge over some river out in the county. It was perfect – isolated, no traffic or nearby houses. We pulled up to the middle of the bridge on the down-river side of the road and got to work chucking big sacks of sherds over the bridge railing. No sooner had we started than down the road came a long, slow funeral procession led by a police car with its colored lights all lit up. Caught like deer in the headlights, we watched them slowly roll past us on the bridge, the occupants of each car clearly curious to know what on earth we were doing. As the procession disappeared in the distance, we quickly got rid of the rest of the sherds and beat it back to campus.

Along with committing embarrassing dumping violations for the archaeology lab, we also occasionally got creative with the displays upstairs in the museum. By far the best example came out of the project to update the Mesoamerican artifact display cases. My peers, who remain unknown, did an excellent, wholly professional job except for an innocuous pair of artifacts in the corner of one case – two small clay disks labelled “Aztec Contact Lenses”. It appeared that the person or persons working on that case had taken some of the red clay from behind the lab, smooshed it around with their fingers until they had two pellets the size and shape of contact lens, prepared a nice museum label for them, and added them to the display. To the best of my knowledge, no visitor remarked on these absurd “artifacts”.

The archaeology lab soon became my home away from home at Ole Miss. Fellow undergrads who were also regulars at the lab included Jason Fenwick, Shelia Landreth, Sam Brookes, and Anne Gatewood. Janet Ford, who was a year or two ahead of the rest of us, was often in the lab before she left for grad school. John Connaway and Sam McGahey, archaeology grad students, were in and out of the lab in connection with their MA research projects. A few years older and with the archaeological experience that we lacked, we learned a lot from them.

L-R, Janet Ford, Bob Thorne, me, and Jason Fenwick posing for a newspaper feature on Ole Miss archaeology. Clarion-Ledger, 4 Apr 1967.

There were, of course, other students in the program, but so much time has passed that all I remember of many of my fellow undergrads are their faces or personal quirks; their names were long ago forgotten. What, for example, was the story about Mona from Sardis and why did she have a British accent? Who was the visiting professor that hosted a wine and cheese social for the undergrads and found all the fish in his aquarium dead the following morning? Did he ever discover who threw up in it? What happened to the girl who, having gotten fed up with the university policy that women must sign in and out of their dorms at night, decided to call it like it was and signed out one evening for “roadside park”?

Mention of the archaeology lab brings to mind Calvin S. Brown’s important contribution to Mississippi archaeology, to which Johnson and Crawford draw attention in the first paragraph of their brief history. Throughout my time at Ole Miss, Brown’s field notebooks and some of his correspondence were still tucked in a lab filing cabinet drawer. I whiled away several hours reading through Brown’s brittle, yellowing notes when I should have been studying for exams. I hope they have now found a more appropriate home in the university archives.

When Francis James joined the faculty in 1966, she offered an upper level course on Middle East culture and society. It only drew a small group of students, and James wisely taught it as a seminar. I recall it as a good class, especially the days when we successfully diverted her from the Middle East and got her talking about British archaeology. It also stands out in my memory as a class for which the required reading included a book that, while it is fundamental to one’s understanding of the Middle East, was easily the most boring book it has ever been my misfortune to read.

Thanks largely to Dr. James’s efforts, several eminent British archaeologists visited Ole Miss during her time there. I particularly recall Leslie Alcock‘s visit at James’ invitation. Perhaps the premier archaeologist of early medieval Britain of his generation, we undergraduates did not have a clue to his stature in the field of archaeology. He was an easy guest and we treated him like he was someone’s uncle. To the best of my recollection, Sam Brookes, Shelia and I spent a day with Dr. James and Alcock on a quick tour of Mississippian mound groups in the Delta guided by Sam McGahey. Along the way, Alcock talked about his work at Cadbury Castle and other important British excavations and we shared with him what little we knew about the Mississippian sites we visited. We ended the day with a stop for fried catfish at Conway’s Place on Moon Lake. Had I known that this modest man had also spent his war as a Captain in the 7th Gurkha Rifles, I would have been happy to skip over archaeology and just talk about the Gurkhas.

Fired up by my growing interest in Lower Mississippi Valley archaeology, I got a summer job (1967) on a University of Missouri archaeology project supervised by Ray Williams in the Mississippi Delta region of Southeast Missouri. By coincidence, John Connaway was Ray’s field assistant that summer and I got to know him well. John volunteered to cook for us both (possibly after he saw me try my hand in the field camp kitchen) and thanks to his kindness and hard work I ate well. I will never forget John’s elaborate tale about his attempt to crossbreed chickens and guinea hens. I almost believed it. That two Ole Miss students just happened to end up on Ray’s crew undoubtedly owed something to Bob Thorne’s growing professional connections at University of Missouri.

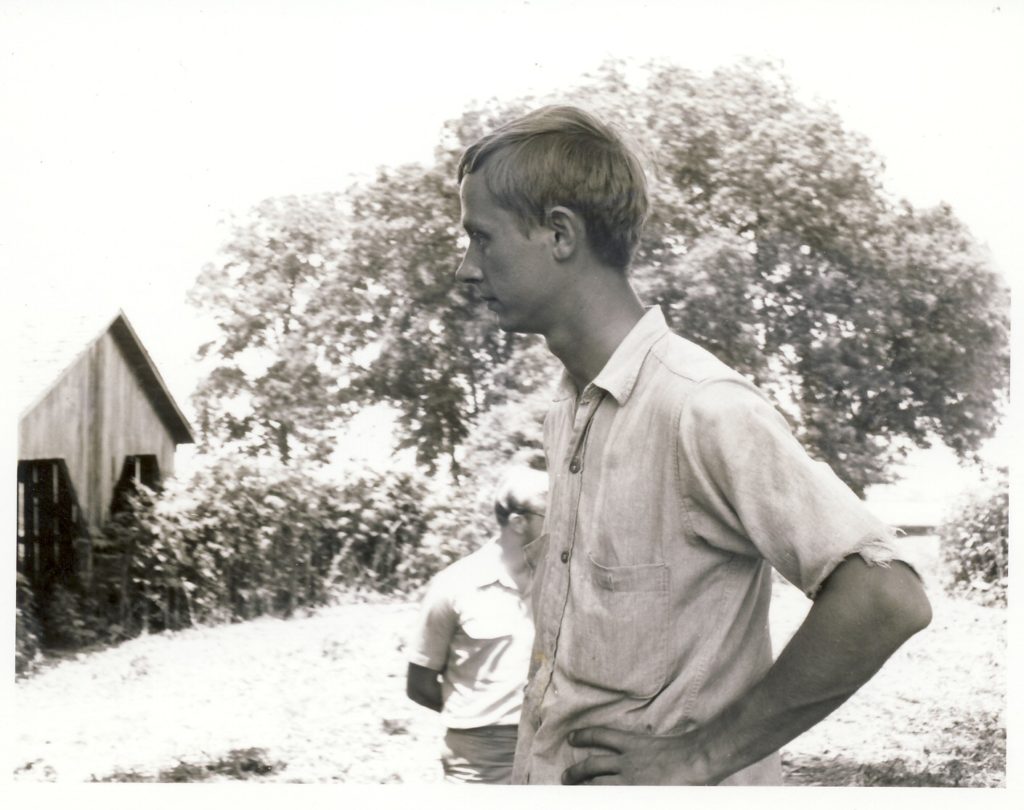

At the Story Mound site, Wolf Island, Missouri. John Connaway is behind me looking in the other direction. June, 1967.

Sam McGahey, an older, quiet grad student who was often in the archaeology lab, was a skilled flintknapper. He always seemed to have a projectile point or two in his pocket that he had either just made or was working on. Some of these points were of a french blue glass, which he said worked easily. His source material, I learned, came from a pool hall on Van Buren St. near the Square. A former car dealership, the building’s street-side wall was made of glass panels, the lowest row of which were thick blue glass. Pool halls being what they are, a panel or two would occasionally get broken and Sam recycled the fragments as reproductions of Native American artifacts.

One temporary instructor overlooked in Johnson and Crawford’s history was Charles H. Nash, then Director of Chucalissa in Memphis and one of the guiding lights for the creation of the anthro program at Memphis State University (McNutt 1969). Chuck enjoyed a brief tenure at Ole Miss, first as a graduate student and then as an instructor hired to teach an intro physical anthro class. I began the semester knowing nothing about him or his background and I am sorry to say that I didn’t take Chuck seriously until the first hourly exam in which I scored the only “D” grade I ever received on an anthro test. It caught my attention and I buckled down. As I worked, I gradually became aware that Chuck not only knew his material, he also knew far more about Southeastern US archaeology than anyone else on campus, mostly because he had directed many of the important WPA-era excavations. I spent the last half of the semester pretty much in awe of the man, and I worked hard to prove to him that I was more capable than the “D” suggested. I finished the semester with a decent grade and I looked forward to seeing more of Chuck and to hearing more stories about his WPA days. Regrettably, his health, which was not good, quickly deteriorated and he passed away later that year.

About halfway through the spring semester, 1968, Tom Koehler asked if I would be interested in working in Mexico for the summer. He explained that Ed Sisson, an Ole Miss alum in the PhD program at Harvard, needed a field assistant. I happily went off to southern Mexico feeling very lucky indeed. Ed could have easily chosen as his assistant any one of hundreds of Harvard students who would have been eager to go, but he reached back to help someone at his alma mater. It was a great summer with plenty to learn, an awful lot of hard work, and I wouldn’t trade the experience for anything. I learned more of practical value working for three months with Ed than I would have learned sitting in a classroom for two or three years. While I hope that my participation helped him to complete his fieldwork, I cannot help but feel that I got the better end of the bargain. I returned from the summer energized and ready to finish up at Ole Miss and start grad school.

Although I graduated and left Ole Miss at the end of the spring semester, 1969, my association with the program felt like it continued for several more years, largely because of Bob Thorne. He entered the PhD program at the University of Missouri (UMO) in the fall of 1968 and planned to return to the Ole Miss faculty when he was done. Reasoning, I guess, that if it was good enough for Bob, then we ought to go there too, Anne Gatewood, Shelia Landreth, and I also applied for admission to the UMO graduate program in anthropology, where we were soon accepted.

Shelia and I were married in August, 1969, at the church in College Hill, Mississippi. Both of us eventually completed our MAs at UMO, after losing a couple of years to the Vietnam War along the way. Shelia went on to pursue her PhD at the University of Tennessee but left before completing her degree. She spent most of her career with the US Army Corps of Engineers at Vicksburg. After I left the army, I did my PhD in anthropology at the University of Illinois (UIUC), where I was hired as an assistant professor a year later. I retired from UIUC as a full professor in 2007. Anne Gatewood married a fellow grad student at UMO and left archaeology in the 1970s. She passed away a few years ago, a life-long Ole Miss fan. Jason Fenwick moved to the UK after graduation and, presumably aided by Dr. James’ many contacts, worked for several years on important archaeological projects there. He later returned to the US, took his MA in anthropology at the University of Kentucky, and went on to become a well-respected architectural historian (Hockensmith 2002). He passed away in 2000 and is remembered by the Louisville Historical League in its annual Fenwick Lecture Series. Sam Brookes enjoyed a long archaeological career in Mississippi, retired from the US Forest Service, and is known to everyone who knows anything about Mississippi archaeology. John Connaway and Sam McGahey both spent their careers with the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, where they made many valuable contributions to archaeology and historical preservation in our state.

To say that the Ole Miss Anthropology program influenced the course of our lives does not do the department justice. Tom, Bob, Dr. James, Chuck, Ed and the other Soc/Anth department members mentioned in this note had a huge impact on us undergrads. Unlike the faculty of many university programs, they treated us as people, not as numbers or irrelevant cheap labor. They patiently answered every dumb question. They constantly worked their professional contacts to find us new opportunities during the summers and after graduation. They stretched the program’s few resources to the breaking point during the school year to help us gain field and lab experience, attend professional conferences, meet archaeologists at other schools, and the like. They were true mentors. It’s a pity that we were all so young and ignorant as students that we did not fully appreciate and acknowledge then what awfully nice people they were (and are).

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Sue for taking time out from tending to her broken arm to critique my first draft and to Shelia for filling in the blanks where my memory failed.

References Cited

Hockensmith, Charles, ‘In Memoriam: Jason McCool Fenwick’, The SAA Archaeological Record, 2.3 (2002), 38

Johnson, Jay K. and Crawford, Jessica Fleming, ‘A Brief History of Archaeology at Ole Miss (Mississippi Archaeological Association Newsletter, 58.2, August 2022)’ (2022). Faculty and Student Publications. 3. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/socanth_facpubs/3

McNutt, Charles H., ‘Charles H. Nash, 1908-1968’, American Antiquity, 34.2 (1969), 172–74

I was at Ole Miss from ’62, graduating in ’66 earning a degree in Anthropology. Koehler & Thorne were top notch not to mention the visiting luminaries from Columbia. Great program…